flyer

description

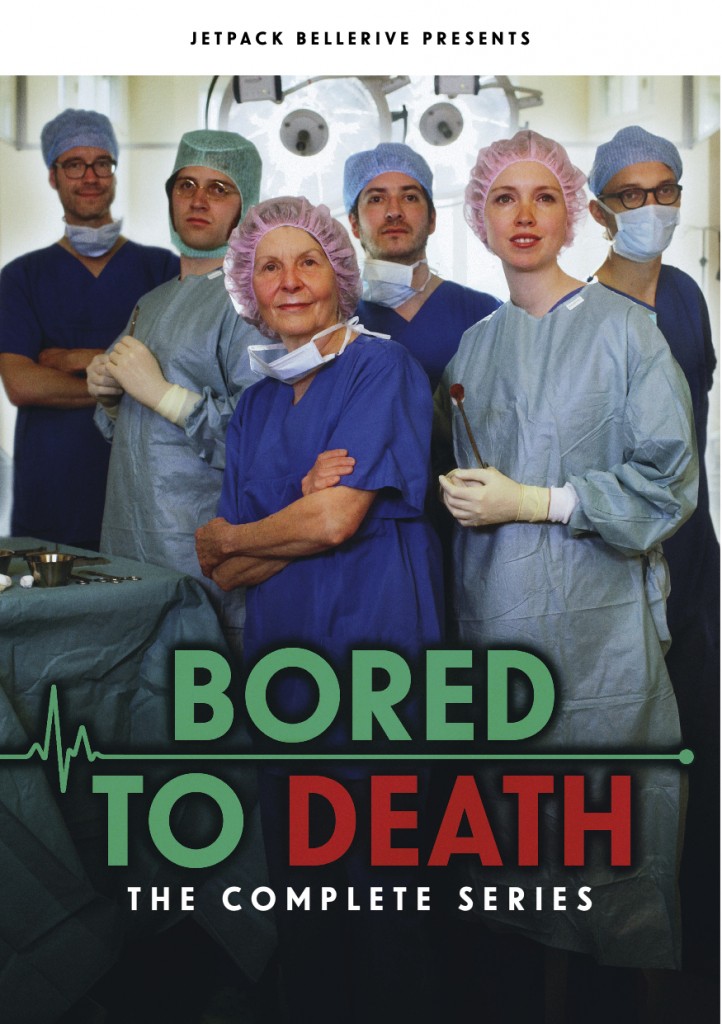

After The Mistake I Am, a second multimedia project entitled BORED TO DEATH is emerging from the collective Jetpack Bellerive. This project involves 2 musicians, 9 composers, 4 artists and an academic, with artistic direction by participating musicians Noëlle-Anne Darbellay and Samuel Stoll and artist Francisco Sierra.

composers: Stephen Crowe (b.1979 UK) Timothy McCormack (b.1984 USA) Aleksandra Gryka (b.1977 PL) Juliana Hodkinson (b.1971 UK) Max Murray (b.1980 CAN) Michael Pelzel (b.1978 CH) Niklas Seidl (b.1983 D) Lars Werdenberg (b.1979 CH) Stefan Wirth (b. 1975 CH) artists: Taus Makhacheva (b.1983 RUS) Shana Moulton (b.1976 USA) Camillo Paravicini (b.1987 CH) Francisco Sierra (b.1977 CH/CL)

academic: Dr. Philipp Schulte (b. 1978 D)

For BORED TO DEATH these composers and artists engage with TV series and translate this into artistic form. The topic of the TV series – a subject that is societally relevant – is brought into a completely new context. The form and manner of translation have been left entirely up to each composer and artist. In so doing, only one condition must be fulfilled: the piece must deal with the products of popular television seriality. Contemporary music meets contemporary television; anti-narrative formal art encounters an epic narrative format; and the acoustic search for the unfamiliar meets a visual medium that continually constructs and replicates that which is all too familiar. A transformative encounter could not be any more different – which is exactly what makes the project BORED TO DEATH so exciting.

At the heart of the project are 9 new works (premieres) for violin and horn. From the outset of the project there will be intensive collaboration between the musicians and the composers. The two video artists, Moulton and Makhacheva, will also create their works using the two musicians as actors. Artists Sierra and Paravicini are developing interventions that will be presented live within the project, to complete the performanceconcert.

program

Camillo Paravicini: Operation (Video)

Juliana Hodkinson

Previously, on for violin and horn

Camillo Paravicini: Intro (Video)

Stefan Wirth

Breaking Bad for violin and horn

Francisco Sierra: Bean Ballet (Intervention)

Lars Werdenberg

Kojak-Berceuse for violin, horn and countertenor

Dineo Seshee Bopape: every spectator is either a coward or a traitor (Video)

Aleksandra Gryka

Boredomsneakattackrunsatisfaction for violin and horn

Stephen Crowe

Dial 9, Merlin for violin and horn

Francisco Sierra: Isobel and Violet (Intervention)

Max Murray

Gaddis’ Grin – Nero’s Violin for two performers and video

Taus Makhacheva: Rehearsal (Video)

Timothy McCormack

I REMEMBER YOU for violin and horn

Francisco Sierra: Aqua (Intervention)

Niklas Seidl

Schiffe for violin, horn and video

Michael Pelzel

Alf-Sonata for violin and horn

essay by dr. philipp schulte

Playing with familiarity and what cannot be anticipated in narrative and anti-narrative seriality.

In ordinary life one has known pretty well the people with whom one is having the exciting scene before the exciting scene takes place and one of the most exciting elements in the excitement be it love or a quarrel or a struggle is that, that having been well known that is familiarly known, they all act in acting violently act in the same way as they always did of course only the same way has become so completely different that from the standpoint of familiar acquaintance there is none there is complete familiarity but there is no proportion that has hitherto been known, and it is this which makes the scene the real scene exciting, and it is that leads to completion, the proportion therefore it is completion but not relief. A new proportion cannot be a relief.

Gertrude Stein, Plays

ʻBored to Deathʼ is the title of a television series produced for the US pay-TV channel HBO, which is known for high quality television. The series is about a writer named Jonathan Ames who starts to work as a private detective on the side. It is described as a noir-otic comedy, a play on words with the film noir genre and the adjective ʻneuroticʼ – which hits the nail on the head. Episode after episode the viewers experience Ames, the anti-hero, embroiled in an endless game of desire and the compulsion to repeat.

In this the latter, the compulsion, is most visible in Ames and his continual failure: not only as an unsuccessful writer; but also private detective; indeed even subsequently as a lover. The former, the desire, is particularly located with the viewers who never grow tired, despite, or maybe even because of, their continually increasing acquaintance, as they watch, with all possible slight variations in failure, who tune in again next time to experience anew this familiarity in a (still) unfamiliar form.

ʻBored to Deathʼ sounds like wearying criticism, as is still applied now and then to so-called New Music with its experiments in form and structure. It is certainly not the case that it is always unfounded, but the accusation nonetheless misjudges what this broad field of contemporary musical currents is about: sometimes radical extensions of the tonal, harmonic and melodic means and forms; the search for new sounds, new forms; or for novel ways to connect old styles. Thus it is the very thing that should bore the listener the least: it is about the unknown, which distances itself from the familiar.

ʻBored to Deathʼ is also, however, the title of a music project by the music performance duo ʻJETPACK BELLERIVEʼ, Noëlle-Anne Darbellay and Samuel Stoll, who have invited nine contemporary composers to each write them a piece of music. Only one condition had to be fulfilled: the piece should in some way engage with the product of serial television. Contemporary music meets contemporary television, an anti-narrative art form meets an epic narrative form and the acoustic search for the unfamiliar meets the unceasing construction and repetition of that which is all too familiar. A transformative confrontation could not compare two less similar entities – exactly why this project is so exciting.

No genre of narrative presentation has developed as much in the past 15 years as the television series. They were first broadcast decades ago, initially on the radio, then on television, ongoing stories with consistent cookie-cutter characters in stand-alone and always similar, standardised episodes that could be produced economically and that were shown daily or weekly. Since about the late 1990s they have developed into series – produced often with an investment equivalent to that of a film – that are more profound, compelling and thoughtful than was the case with earlier Telenovelas, soaps and other series. ʻQuality TVʼ is the buzzword developed in this context, and it also describes – though not exclusively these – the television series that the US pay-TV broadcaster HBO produces for a demanding, paying public according to their slogan ʻItʼs not TV. Itʼs HBOʼ. These include the comedy format ʻBored to Deathʼ and numerous other series viewed worldwide such as the critically celebrated ʻThe Wireʼ, the high-gloss trash vampire saga ʻTrue Bloodʼ or the Mafia epic ʻThe Sopranosʼ. By now an enormous audience is under the spell of series like these that have long ceased to be only on television but are also consumed via DVD and online distribution.

But as impressively and swiftly as the narrative art of television has developed in recent years, and continues to do so, so the role of music in television series, if you listen carefully for it, seems unable to keep up with the speed of progress. The reason for this may be obvious: linguistic expertise – the writing of slick, incisive dialogues, the creation of complex narrative forms – now dominates production of the series format, as it always did. These series are later given filmic visual form and only then can the musical contribution be composed.

So composers are at the end of a long sequential chain: producer – author – director and finally the input of music segments as often determined by the editor in the cutting room using what is, as a rule, pre-recorded material. This approach can be observed in ʻquality TVʼ formats such as the mass murderer series ʻDexterʼ – a series, with a suitably serial killer as its protagonist, the plot of which thus brings gripping variations on the formal theme to fruition again and again. As much as familiar themes and sequences are transformed so they vary from episode to episode in order to achieve – at least that is the aim – a continual escalation of tension, the contribution of the music hardly changes. The music is produced as it has been done for decades in many television series: a composer writes a soundtrack consisting of a title song with a high recognition value, as well as pieces for various standard situations – something for exciting moments, something for moments of reflection, a lighter theme for comic scenes, something for the tragic sequences – and this pool of tracks is only minimally enlarged upon in the course of the episodes. So while the characters and the complex plot lines are given significant scope to develop over the years a series like ʻDexterʼ runs (at least they have been in many productions from the last 15 years,) when it comes to the contribution of the music, usually only considered as having an accompanying role, there is continual recourse to the standard material which has scarcely changed from the first episode.

Both the reason for and the consequence of this is the aforementioned dominance of narrative in serial TV formats. The plot and the atmosphere and connections it creates dominate; all remaining means of presentation, particularly the music, serve above all to accompany it, and therefore, all too often, to simply affirm that which is being narrated. This applies to the filmic – the images – though it can be stated that many directors achieve ever greater emancipation from the plot and its concrete situations at this level; a particularly notable example in this context is ʻBreaking Bad, a series about a chemistry teacher who advances to become an arch criminal. In numerous episodes the viewer can observe how the camera examines close-up details and adopts unusual perspectives while the action takes place elsewhere, often peculiarly slowly, as if by the by.

Of course these series live by the quality of their scripts and actors – yet, in truth, thanks also to their emancipated visual filmic language, intensive application of colour and surprising camera angles. And in part something similar is attempted with the soundtrack, and succeeds, but only partially succeeds. In general, as is the case with many high-gloss series, the standard is that any surprises through variation and transformation occur at plot level, not at the level of images or even music. The latter still seems to be bound to the tradition of the classic serial format, for which one thing counts above all: a high degree of familiarity. Clearly this is for economic reasons – if it works through repetition, then it must not be created again – but also due to a viewpoint that seems widespread among programme makers and editors, that something that pleased the public once must please them a second time, thus guaranteeing high viewing figures: ʻNever change a winning formula!ʼ

The opposite tendency can be argued – for serialism in New Music for instance; it has nothing to do with a high degree of familiarity. The music by composers like René Leibowitz, Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen which further advanced developments by Arnold Schönberg and Anton Webern at the end of the 1940s and in the first half of the 1950s can be appreciated not so much as a style or technique but as a method of thinking about composition. The idea of non-linear systems of ordering, such as those in the works of Webern and Schönberg that were organised predominantly using the structure of pitch, was to be expanded into all other musical parameters, such as duration and volume, acoustic colour, dynamics, rhythm and rests. All musical qualities were to be clearly defined according to predetermined series of numbers and proportions, which meant that both the creative ego of the composing subject and his or her artistic intention and personal taste were largely repressed. In relation to Boulezʼ ʻStructures Iʼ György Ligeti once spoke of a ʻbeauty in the opening of pure structuresʼ. With this ʻthe composition would lose its character as a ʻwork of artʼ: at the same time composing would become the research of the newly conceived connections within the materialʼ. 1

The unfamiliar, the surprising and the unexpected cannot be approached in a more radical form: the idea of Serial Music stands for the search for new, to date unheard-of compositional results, which can only be achieved by deactivating the habits of the artist-subject. No attention is paid here to either conventional dramaturgical forms or the assumed taste of the listeners. And it is self- evident that the resulting tonal unfamiliarity occurs in the (in the Hegelian sense) content-less, non- specific field of instrumental music: no narrative, anywhere, whose rules would make the music secondary – that would conflict with the pure dominance of the structure. So while in the format of TV series music remains as much as possible subordinate, conforming with its role as a guarantor of recognition and familiarity as is required, in New Music, serialism, with its content-less tonality and related approaches, puts the greatest value on a completely free musicality, obeying only its own structural logic, as far as possible from any familiar form.

And at this very juncture the group JETPACK BELLERIVE puts forth the project ʻBored to Deathʼ: Noëlle-Anne Darbellay and Samuel Stoll set out to find the familiar in the field of the unfamiliar – and as a result experience something very different to a television series, which tries to present the familiar in ever new ways, but also very different to Serial Music, which is bent on the completely unfamiliar and structural novelty. ʻBored to Deathʼ creates a dialectic relationship between the familiar and the unfamiliar; in so doing the project never submits to the not least economical formal conventions of television, but nonetheless never denies the indisputable attraction that television emits.

And more too: in many of the compositions there is a deliberate engagement, musically and instrumentally, thus principally anti-narratively, with narrative phenomena. The basic rules and structures of narrative are at once nullified and at the same time sounded out. The music is not less significant than the narrative here, like in the vast majority of TV series formats; instead narrative remnants are carried over into the realm of musical structure and dissected there. Thus a transformation and variation of the initial material takes place which is relevant to the serial, because it orients itself towards the conditions of the original medium, but does so on a purely formal level, not on that of content. And who knows, in time or ʻcoming upʼ, one could say, a return to the medium of the filmic may take place, the discovery of a new kind of serial, which no longer functions according to the rules of narrative: to be continued.

Maybe in their project JETPACK BELLERIVE are approaching what Gertrude Stein, the inventor of the serial ʻconveyor belt of word productionʼ, identifies, in the quotation that introduces this text, as absolute familiarity, but a kind of familiarity that adopts a hitherto completely unfamiliar relationship to the Other.2 Excitement does not make space for relief here, as Stein writes, because the new proportions allow no relief. Instead they are complemented, fulfilled and brought to a peak – because it all is as it always was, but it is located in such an unfamiliar, such a new context, that this relationship between that which is all too familiar (yes, that which is boring) and the unsettling Other (and death remains the most unsettling of all) generates an enjoyable tension that sometimes becomes almost unbearable.

Thus Darbellay and Stoll are moving along very similar dialectic paths to Jonathan Ames in the HBO series, he who leaves his familiar surroundings as a writer in order to find the diversion he longs for in life as a private detective – and in so doing chooses a profession in which the key skill is to discover order in chaos and familiar structures in the unfamiliar. Thus both (Ames and Jetpack Bellerive) establish new relationships between that which you believe you know and that which is effectively unfamiliar. May Stoll and Darbellay be granted more success than their neurotic forerunner!

dates and venues

06.11.2014 Kunsthalle St.Gallen

09.11.2014 Alass Zofingen, Kulturraum Hirzenberg

13.11.2014 Kunsthalle Bern

22.11.2014 Südpol Luzern, Forum neue Musik Luzern

29.11.2014 Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts Lausanne

04.03.2015 London, Brunel University

21.04.2015 Berlin, Unerhörte Musik im BKA

23.04.2015 Zürich, Walcheturm

24.04.2015 CentrePasquArt Biel, Festival l’art pour l’Aar

30.10.2015 Hannover, Sprengel Museum

photos

with kind support by

Ernst Göhner Stiftung

Fachausschuss Musik Kanton Basel Stadt Musik

Fondation Isabelle Zogheb

Fondation Nestlé pour l’Art

Kanton St.Gallen Kulturförderung

STEO Stiftung

SIG Schweizerische Interpretengenossenschaft

Fondation Nicati-De Luze

Klinik im Spiegel Bern